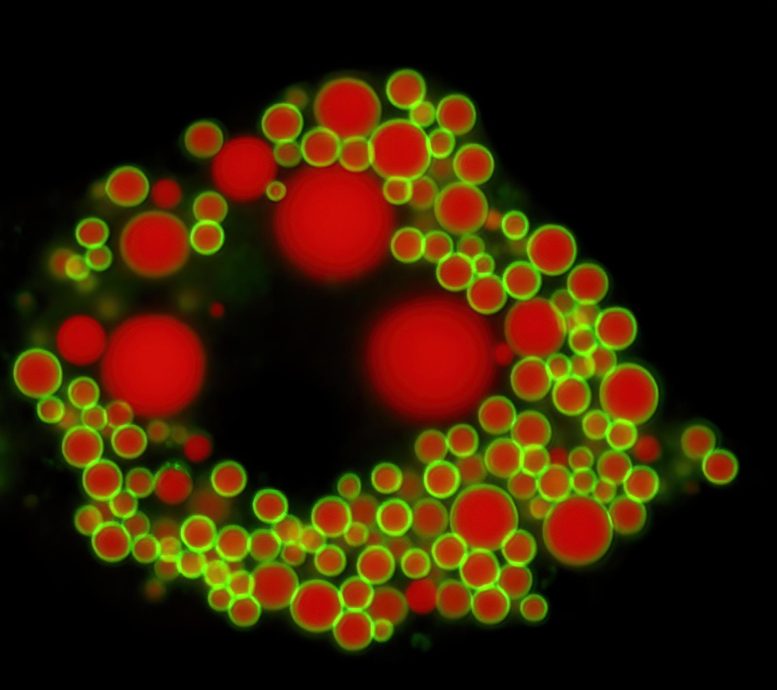

Gotitas de lípidos en la célula de grasa del ratón: la membrana de las gotitas se tiñó de verde y los lípidos almacenados en ellas se tiñeron de rojo. Crédito: Johanna Spandl / Universidad de Bonn

El estudio proporciona la primera comprensión rigurosa de los procesos críticos de remodelación en el tejido adiposo.

Las células grasas utilizan moléculas de grasa como medio para almacenar energía. Estas moléculas están compuestas por tres ácidos grasos unidos a un esqueleto de glicerol y se conocen comúnmente como triglicéridos. Durante mucho tiempo se ha creído que estas moléculas experimentan cambios continuos durante el almacenamiento, ya que se descomponen y reconstruyen regularmente, un proceso conocido como el «ciclo de los triglicéridos». Pero, ¿es correcta esta suposición y, de ser así, cuál es el propósito de esta operación?

«Hasta ahora, no ha habido una respuesta real a estas preguntas», explica el profesor Christoph Thiel del Instituto Limes de la Universidad de Bonn. «Es cierto que ha habido evidencia indirecta de esta reconstrucción permanente en los últimos 50 años. Sin embargo, todavía no hay evidencia directa de eso».

El problema: para demostrar que los triglicéridos se descomponen y que los ácidos grasos se modifican y recombinan en nuevas moléculas, sería necesario rastrear su transformación a medida que viajan por el cuerpo. Sin embargo, hay miles de formas diferentes de triglicéridos en cada célula. Por lo tanto, es muy difícil hacer un seguimiento de los ácidos grasos individuales.

La etiqueta hace que los ácidos grasos no sean ambiguos.

«Sin embargo, hemos desarrollado un método que nos permite adjuntar una etiqueta específica para los ácidos grasos, haciéndolos inequívocos», dice Thiel. Su grupo de investigación marcó diferentes ácidos grasos de esta manera y los agregó a un medio de cultivo para células grasas de ratón. Luego, las células de ratón incorporaron las moléculas marcadas en los triglicéridos.

«Hemos podido demostrar que estos triglicéridos no permanecen iguales, sino que se descomponen y se vuelven a formar continuamente: cada lípido[{» attribute=»»>acid is split off about twice a day and reattached to another fat molecule,” the researcher explains.

But why is that? After all, this conversion costs energy, which is released as waste heat – what does the cell get out of it? Until now, it was thought that the cell needed this process to balance energy storage and supply. Or perhaps it is simply a way for the body to generate heat.

“Our results now point to a completely different explanation,” Thiele explains. “It’s possible that in the course of this process, the fats are converted to what the body needs.”

Poorly utilizable fatty acids would consequently be refined into higher-quality variants and stored in this form until they are needed.

Fatty acids consist largely of carbon atoms, which hang one behind the other like the carriages of a train. Their length can be very different: Some consist of only ten carbon atoms, others of 16 or even more. In their study, the researchers produced three different fatty acids and labeled them. One of them was eleven, the second 16, and the third 18 carbon atoms long.

“These chain lengths are typically found in food as well,” Thiele explains.

Short fatty acids are eliminated, long ones “improved”

Labeling allowed the researchers to track exactly what happens to the fatty acids of different lengths in the cell. This showed that the fatty acids consisting of eleven carbon atoms were initially incorporated into triglycerides. After a short time, however, they were split off again and channeled out of the cell. After two days, they were no longer detectable. “Such shorter fatty acids are poorly usable by cells and can even damage them,” says Thiele, who is also a member of the Cluster of Excellence ImmunoSensation2. “Therefore, they are disposed of quickly.”

In contrast, the 16- and 18-atom fatty acids remained in the cell, although not in their original fat molecules. They were also gradually chemically modified, for example by additional carbon atoms being inserted. In the original fatty acids, the carbon atoms were moreover linked with single bonds – roughly like a human chain in which neighbors join hands. Over time, this sometimes developed into double bonds – as if revelers at a party were doing a conga. The fatty acids that are formed in this process are called unsaturated. They are better utilizable for the body.

“Overall, in this way the cells produce fatty acids that are more beneficial to the organism than those that we had originally supplied with the nutrient solution,” Thiele emphasizes. In the long term, this results for instance in the formation of oleic acid, a component of high-quality olive oil, from palmitate, such as that contained in palm fat. However, the cell cannot change the fatty acids as long as they are inside the fat molecule. They must first be split off, then modified, and finally tacked back on. Thiele: “Without triglyceride cycling, there is also no fatty acid modification.”

Adipose tissue can therefore improve triglycerides. If we eat and store food with unfavorable fatty acids, they do not have to be released in that state again when we are hungry. What we get back contains fewer “short” fatty acids, more oleic acid (instead of palmitate), and more of the important arachidonic acid (instead of linoleic acid). “Nevertheless, we should take care in our diet to consume high-quality dietary fats as much as possible,” the researcher stresses.

Because the refinement never works 100 percent. In addition, some of the fatty acids are not stored but used directly in the body. In the next step, the researchers now want to test whether the same processes occur in human adipose tissue as in individual mouse fat cells in the test tube. They also want to find out which enzymes make cycling work.

Reference: “Triglyceride cycling enables modification of stored fatty acids” by Klaus Wunderling, Jelena Zurkovic, Fabian Zink, Lars Kuerschner and Christoph Thiele, 3 April 2023, Nature Metabolism.

DOI: 10.1038/s42255-023-00769-z

The study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

«Alborotador. Amante de la cerveza. Total aficionado al alcohol. Sutilmente encantador adicto a los zombis. Ninja de twitter de toda la vida».

More Stories

Estudio: la actividad de las proteínas cancerosas aumenta el desarrollo del cáncer de próstata

Un nuevo material luminoso puede ser la solución al deterioro de las infraestructuras

Las vesículas extracelulares son prometedoras en el tratamiento de lesiones pulmonares y cerebrales durante el nacimiento