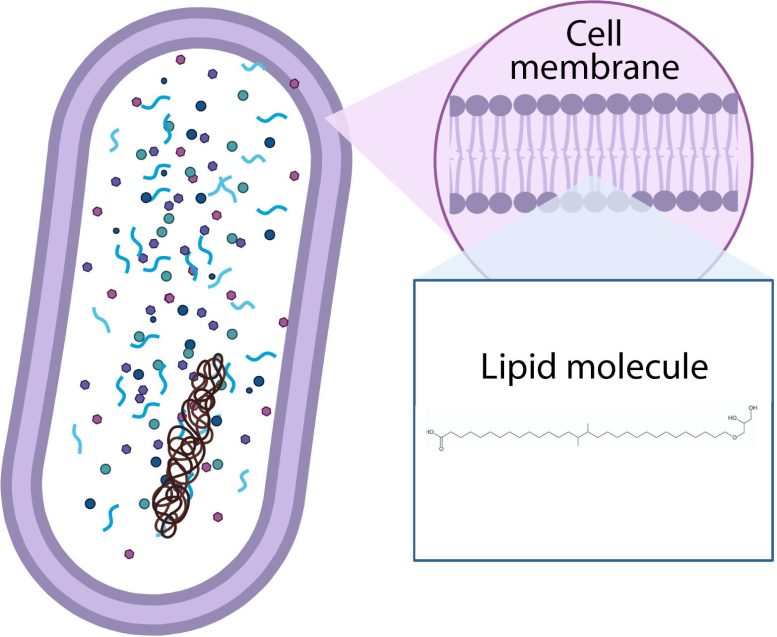

Los lípidos forman la membrana del microbio. Crédito: Diana Sahonero, Noticias

La pieza que falta en la reconstrucción de la historia del clima de la Tierra también proporciona una nueva comprensión de la evolución temprana de la vida.

Las pieles microbianas hechas de lípidos o partículas de lípidos podrían conservarse como fósiles y revelar información sobre las vidas pasadas de estos microorganismos.

«Algunos lípidos microbianos se usan ampliamente para reconstruir climas pasados. Durante mucho tiempo han estado envueltos en el misterio, porque no sabíamos qué microbios los produjeron y en qué condiciones. Esta falta de información limita el poder predictivo de estas moléculas para reconstruir ambientes pasados. condiciones», dice Sahonero.

Su estudio muestra las bacterias que producen estos lípidos y cómo han desarrollado su capa externa basada en lípidos para adaptarse a entornos cambiantes, mejorando aún más nuestra capacidad para reconstruir y predecir el cambio climático con mayor detalle.

Reconstrucción climática

Los lípidos, los componentes básicos moleculares de la membrana celular, son exclusivos de cada microbio.[{» attribute=»»>species. “It works just like fingerprints, they can be used to identify microbial remains,” says Laura Villanueva, associate professor in the Faculty of Geosciences at Utrecht University and senior scientist at NIOZ. The lipids of ancient microbes can be found in old sediments. Once these molecules from the past are separated, identified, and related to currently living groups of bacteria, the lipids can work like ‘biomarkers’. These markers can tell us about the atmospheric and oceanic conditions of the ancient earth because we know from the living relatives of the microbes how they interact with their environment.

Set-up of the growth experiments in serum bottles without oxygen for obtaining samples for omics analysis (lipidomic, transcriptomic, and proteomics). Credit: Diana Sahonero, NIOZ

Who made these molecules and how?

For a long time, it was unclear precisely which bacteria were making these specific lipids, called branched Glycerol Dialkyl Glycerol Tetraethers (GDGTs). This type of lipids are often used in climate reconstructions. Diana and her colleagues have finally discovered the bacteria forming these lipids. And also how these bacteria actually make the lipids. “It was like looking for a needle in a haystack”, says Sahoreno. “From the start, we knew we had to answer this question with a massive approach. We needed to investigate more than 1850 proteins to identify microbes making these lipid molecules.”

Fluorescent microscopy image of a bacterium forming membrane-spanning lipids utilized as a model organism in this study. Thermotoga maritima cells stained with a DNA dye (DAPI) (Left panel) and with a membrane dye (FM4-64) (Right panel) simultaneously. Credit: Diana Sahonero, NIOZ

Once researchers know which currently living bacteria make these lipid molecules, they can be used to make more accurate climate reconstructions. Researchers can measure the interactions of these living bacteria with their surrounding seawater or atmosphere. This information leads to ‘proxies’ – keys to correlate details of the lipid molecules (abundance for instance) to values of the environment. This is an important step in reconstructing past environmental and climate conditions, based on old sediment samples.

Early evolution of life

“Our study indicates that there are many species of currently living bacteria that can make these types of membrane lipids. Also, we found that those bacteria are all limited to environments where oxygen is absent,” says Sahonero. “This study into archaeal-like lipids of bacteria shows how this group of microbes that produces them evolved their lipid membrane billions of years ago. It is fantastic to get a glimpse of this part of life’s history. It was mostly a mystery until now.”

What next?

The work of Sahonero and her colleagues is still ongoing. “Now we know which bacteria form these molecular building blocks and we understand how they do that. Next, we need to find out how the production of these molecules depends on environmental factors like water temperature or pH,” says Villanueva. “Then, the proxy based on these bacterial lipids can be used more confidently by (paleo)climatologists. This gives them new possibilities to reconstruct and predict climate change in more detail.”

Reference: “Disentangling the lipid divide: Identification of key enzymes for the biosynthesis of membrane-spanning and ether lipids in Bacteria” by Diana X. Sahonero-Canavesi, Melvin F. Siliakus, Alejandro Abdala Asbun, Michel Koenen, F. A. Bastiaan von Meijenfeldt, Sjef Boeren, Nicole J. Bale, Julia C. Engelman, Kerstin Fiege, Lora Strack van Schijndel, Jaap S. Sinninghe Damsté and Laura Villanueva, 16 December 2022, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abq8652

«Alborotador. Amante de la cerveza. Total aficionado al alcohol. Sutilmente encantador adicto a los zombis. Ninja de twitter de toda la vida».

More Stories

Estudio: la actividad de las proteínas cancerosas aumenta el desarrollo del cáncer de próstata

Un nuevo material luminoso puede ser la solución al deterioro de las infraestructuras

Las vesículas extracelulares son prometedoras en el tratamiento de lesiones pulmonares y cerebrales durante el nacimiento